Virginia’s Loudoun County is widely recognized as the “data center capital of the world,” but it looks like Prince William County is poised to wrest away that title.

Loudoun County has more than 160 data center buildings, with floor space totaling 31 million square feet. That’s about the size of New York’s Central Park. Loudoun County officials say they expect to top out at 40 million square feet in the next decade.

But an analysis by the Prince William Times finds Prince William County will overtake Loudoun County in data center development and go well beyond those numbers.

That’s enough to make Prince William County the data center capital of the world twice over. The question is, how long would it take.

When Prince William County will go to No. 1 is hard to gauge. In recent years, the county has been building about a million square feet of data center space annually, and power availability could become an issue. It will take huge amounts of electricity to power that many data centers.

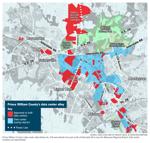

But already, the county has its own data center alley, located mostly inside the county’s “data center opportunity zone overlay district,” an area that comprises more than 10,000 acres designated for data center development.

And construction appears to be on the upswing: The county’s finance office says 4.6 million square feet of new data centers are being built right now.

“Some would say, ‘That’s great; that’s wonderful,’” said newly seated Supervisor Tom Gordy, a Republican who represents the Brentsville District, where much of the data center growth is concentrated. “But with that also comes all the power line infrastructure (and) the development issues, such as blasting rock, vehicle noise, light pollution — things that we’ve been experiencing in my district with current projects under construction.”

Data center opponents cite other concerns as well: the huge buildings that sometimes don’t blend in with neighboring development; the nonstop buzzing that some emit from their air-conditioning systems; their massive power demand; and how all that development and power use could affect the environment.

Consider one impact on the local economy: Gordy said the very high prices data center developers will pay for land has resulted in higher land assessments — and higher taxes — for many businesses.

Another impact of the data center gold rush in Prince William County is that it appears to have gobbled up much of the commercial and industrial land that was once hoped to be available for other industries.

“Try to find land; try to find any land,” said Carter Wiley, a real estate broker who handles data center deals. “There’s no 5-acre land out there. There’s a handful of 1- and 2-acre pieces. And that’s it.”

Data center boom

The rush into Prince William began about a decade ago as land prices in Loudoun reached $2 million to $3 million an acre. Data centers wanted to find cheaper land but still be near Loudoun because the proximity helped the data centers share data in just milliseconds. They were also attracted by Prince William’s lower property tax rates. Democrats who held a majority of the seats on the Prince William Board of Supervisors were captivated by the promise of hefty tax revenue to fund priorities such as school construction and pay raises for teachers, firefighters and other public employees.

But as data centers spread across the county, they kindled fear among conservationists and residents. Eventually, those concerns evolved into angry protests and even lawsuits. The backlash helped unseat Ann Wheeler, the Democratic chair of the board of supervisors and a champion for data centers. Her defeat last year by Deshundra Jefferson, a more data-center-wary Democrat, surprised many observers.

In an interview last week, Jefferson expressed caution about allowing data centers to gobble up more undeveloped land in the county.

“We need to get a handle on what’s in the pipeline,” she said. “We need to get a handle on how we’re taxing them. I mean, we shouldn’t act like we’re so lucky to have them here. We’ve got to treat them as we treat any other business.”

Jefferson acknowledged that data centers have their pluses: They don’t bring a lot of children into the school system, which would require more spending on schools. And they don’t add much traffic to already busy county roads. What they do create is a hefty revenue stream.

Jefferson thinks they should pay even more.

In their upcoming budget talks, the supervisors are poised to discuss raising the data center tax rate another 85 cents to $3 in assessed value. That would generate another $27 million for county services and local schools. Already, data centers and property zoned for them generate about $114 million in annual tax revenue, more than 10 times what they produced a decade ago.

How many data centers are in the works?

Assessing what’s coming is not easy. Two years ago, Bob Weir, then a Haymarket town councilor and now a county supervisor, and Bill Wright, a Gainesville resident, began building a list of data center projects that were underway by scouring public records, press reports and industry announcements.

Since then, the county has provided lists of what’s been built so far and what’s under construction. But a county spokesperson said the county does not have a list of the data centers underway in the data center overlay district, where they can often be built without the supervisors’ approval. Created in 2016, the district covers about 10,000 acres stretching along Va. 234 from Interstate 66 south to the Manassas airport.

For its analysis, the Times consulted Wright and Weir’s list, the county’s development portal, and data center numbers released by the county finance office. Still, the number is inexact, as it depends on availability of accurate data.

John Lyver, a former NASA engineer and now a Prince William planning commissioner, estimates up to 86 million square feet of data center space has been built or is in the pipeline.

“I think it is safe to say over 80 million square feet are either operational or planned,” he said.

What will the effect be?

Part of the concern about data center sprawl is its effect on other commercial development. In May 2022, a consultant hired by Prince William County predicted that the highest demand scenario in the county would result in construction of 48 million square feet of data centers in 20 years.

But the consultant apparently did not contemplate the supervisors approving data centers on land not zoned for data centers and outside the overlay district. That’s what the supervisors did late last year when they approved the Prince William Digital Gateway and the Devlin Technology Park. Together, the projects could bring as many as 46 data centers — 37 in the digital gateway and nine at Devlin. The supervisors used the high-demand scenario in the consultant’s report as a reason to rezone land outside the overlay.

The consultant’s main purpose was to estimate how much space would be available in the county for key “targeted industries,” including office rental, medical offices, industrial uses, warehousing, manufacturing, and data centers. A major concern, repeatedly expressed in its report, was that “the high rate of data center development threatens to crowd out” the county’s other targeted industries.

Jefferson said it’s time the supervisors put some limits on data centers and resisted unchecked growth.

“I’ve said to people, we don’t have to accept every application. It’s okay to put limits, to put guardrails around data center growth in our county,” she said. “These are industrial buildings. We don’t want to end up with incompatible uses” next to homes and schools.

Jefferson said she expects her election to make an impact on slowing growth, as at least half of the eight-member board is now more skeptical of data centers.

“That’s one thing people always say, ‘Well, how are you going to stop it?’ And I just look at them. It’s like, ‘They don’t have the votes,’” she said of her fellow pro-data center supervisors who are accustomed to approving them. “Do you understand (that) with my election, they don’t have the votes?”

Instead of more data centers, Jefferson directed county staff to explore ways to bring more agritourism — farms and other agricultural businesses that cater to visitors — to the county.

“I would love to see if there are businesses that we can bring here that would leverage the land,” she said.

Still, perhaps the best bet to slow data center growth is the industry’s own hunger for power. It has been estimated that the Digital Gateway alone will require between 2 and 3 gigawatts of power — that’s enough to power more than a half million homes.

In the summer of 2022, Dominion Energy found that it did not have adequate transmission lines and substations to power all the data centers being built in Loudoun County. It launched an emergency construction program. But, in the meantime, Loudoun County’s new data centers were forced to start up with only a fraction of the power they had requested. Some held off on building. Some went elsewhere.

Two Dominion executives told the Prince William Times last July that at the time there was enough power for Prince William County’s data centers. They said they believed they had Prince William power demand forecasts well in hand.

But data center developers are looking at the construction boom in Prince William County, and the fact that data centers now use much more power than they did a decade ago, and are not so sure.

“There’s a lot of land that’s never been considered part of the data footprint now being incorporated into that data footprint,” said Wiley, the data center real estate broker. “So, the projections of data center square footage, I think, will well exceed what has ever been discussed. Getting power’s going to be the play here.”

Reach Peter Cary at news@fauquier.com