- By Daniel Berti Times Staff Writer

Who’s left out of the ‘rural crescent?’

Alfredo Panameno/Sky’s the Limit Media, staff photos

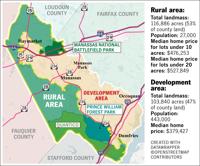

There is a line in Prince William that carves the county into two halves. On one side, there is vast, mostly open space that includes the Marine Corps Base Quantico, Prince William Forest Park and the Manassas Battlefield. It’s home to about 27,000 people.

On the other side, 443,000 people live in an area that runs the gamut from urban to industrial to semi-rural.

The line separating the two areas is known as the “rural area boundary,” part of a land-use policy adopted by the board of county supervisors in 1998 to put the brakes on suburban growth when the county had 200,000 fewer residents. It splits the county into the rural area, or “rural crescent,” on one side, where only one home can be built per 10 acres, and the development area on the other.

And while the population in the development area has increased dramatically since 1998, the rural area’s strict zoning rules have kept it sparsely populated.

Now, some local elected officials and community members say the policy is shutting out lower- and middle-income people and contributing to overcrowding in the rest of the county, while rural crescent advocates fiercely defend it as a land conservation strategy. Meanwhile, officials are reaching a key decision point on rural area zoning as updates to the county’s comprehensive plan are expected in the coming months.

Are the rural crescent rules a form of ‘exclusionary zoning’?

Some supervisors have used words like “segregation” and “exclusionary zoning” to describe the policy – words that carry with them the long legacy of racist housing policies that proliferated in the United States in the 20th century, some of which continue today.

Alfredo Panameno/Sky’s the Limit Media

“If you have a few sections of the county where the only people that can access [it] are people … rich enough to afford a 10-acre lot, that’s already a form of segregation in my opinion,” Supervisor Kenny Boddye, D-Occoquan, said in a recent interview.

Others, like at-large board Chair Ann Wheeler (D) and community activist Rev. Keith Savage, have referred to the rural area policy as a form of exclusionary zoning – a practice historically used to keep racial and ethnic minorities from moving into middle- and upper-class neighborhoods.

Exclusionary zoning often imposes minimum lot sizes and prohibit multi-family dwellings that make certain areas less affordable for low- and middle-income people. But the term is most often used in reference to cities – not exurban and rural areas.

“Our current status quo seems to default to exclusionary zoning. Maintaining 10-acre lots focuses on privilege and hinders affordable, middle-class family inclusion,” Savage said at the board of county supervisors Jan. 19 meeting.

“Exclusionary zoning throughout the western end of the county effects the entire county,” Wheeler said at the same meeting.

Others have raised the issue of equity – the fair and consistent treatment of all individuals – in the context of the rural area. Supervisor Andrea Bailey, D-Potomac, called equity “the elephant in the room” on Jan. 19, as the board debated the Preserve at Long Branch, a controversial 99-home development that was approved by the board’s Democratic majority.

“We have to look at equity. But equity is not preserving a certain spot in our county and then placing the development in other areas of the county,” Bailey said.

Supervisor Margaret Franklin, D-Woodbridge, in an interview, declined to comment about whether she believes the rural area excludes some from living there. But she said, in general, the county’s land-use policies have created a situation where “only wealthy individuals or entities are able to build and live in certain areas.”

“We certainly don’t want any policy that is or resembles anything that is exclusionary for a lot of reasons. Equity is one of those reasons. It creates lack of diversity. And particularly as we talk about land use, exclusionary zoning policies can cause over overdevelopment and overgrowth in certain parts of a particular area. And I think that’s what we’ve seen with some of our current land use policies,” Franklin said.

Rural area: less diverse, more expensive

County demographic data shows the rural area is less racially diverse than the development area, and its homes more expensive.

About 68% of the rural area population is white, compared to only 41% in the remainder of the county, according to Prince William County demographer Brian Engelmann.

The median home price in the rural area for lots under 10 acres is 25% higher than the countywide average. For lots under 20 acres, the price is 38% higher than the countywide average, according to Prince William County Planning Director Parag Agrawal.

Still, advocates for preserving the county’s current rural area policy have bristled at the assertion that the policy excludes some people from living there.

Elena Schlossberg, a local activist and executive director of The Coalition to Protect Prince William County, said in a recent interview that there are “no racial undertones” in the rural area policy. Schlossberg said that land is cheaper in the rural area than in the development area on a per-acre basis, and that expensive single-family homes exist within the development area, often on much smaller lots.

“It is less exclusionary to buy land in the ‘rural crescent’ because it’s cheaper,” Schlossberg said.

Alfredo Panameno/Sky’s the Limit Media

Schlossberg also pointed out that the homes in the “Preserve at Long Branch,” which the county board approved in that Jan. 19 meeting during which exclusionary zoning was discussed, are estimated to sell for $750,000 and up.

“They’re selling homes that will ultimately be a million dollars. How is that not exclusionary?” Schlossberg asked.

Others rural area advocates have noted that several small-lot residential enclaves exist within the rural area that were grandfathered into the 1998 zoning change. Those homes generally sit on lots smaller than 10 acres and are cheaper than the average rural area home.

Alfredo Panameno/Sky’s the Limit Media

“There are smaller than 10-acre lots that exist,” said Supervisor Jeanine Lawson, R-Brentsville. “… It’s not just a bunch of McMansions.”

Prince William County’s former long-range planning director Tom Eitler, who helped create the rural area designation in 1998, said he does not believe the rural area policy is a form of exclusionary zoning. Eitler still lives in the county and is currently senior vice president at The Urban Land Institute, a nonprofit research institute that focuses on land use, real estate and urban development.

“Exclusionary zoning is an overt zoning ordinance that prevents a certain class of people or a certain group of people from buying houses or renting houses in an area. I don’t see anything that resembles that with the current comprehensive plan,” Eitler said in a recent interview. “… That somehow this is racially, or income-based oriented, I don’t buy it.”

Eitler added that he believes there is enough land remaining within the county’s development area to satisfy the residential and commercial needs for at least the next 25 years. Eitler said there are at least 12,000 acres of undeveloped residential land and 14,000 acres of undeveloped commercial land remaining in the development area.

The county did not respond to questions about how much undeveloped land is left in the development area.

Zoning partly blamed for affordable housing crisis

Discussion of exclusionary zoning has come to the fore in Virginia as the commonwealth grapples with an affordable housing crisis. The Virginia General Assembly considered a bill in 2020 that would have legalized “middle housing,” like duplexes and townhouses, in any place currently zoned for single-family homes statewide to address the issue. But the bill was ultimately tabled.

The bill’s sponsor, Del. Ibraheem Samirah, D-86th, of Loudoun, wrote at the time that banning middle housing in certain neighborhoods “chalks up to modern-day redlining.”

A wide-ranging state report on racial inequities in Virginia law released on Feb. 10 recommended imposing limits on exclusionary zoning in localities. Those recommendations include reducing lot-size requirements, increasing housing densities by requiring localities to have a certain percentage of affordable housing and enacting regulatory changes that allow lower-income people to move into a locality.

Prince William County’s planning department has no official definition for exclusionary zoning. But County Deputy Executive and former county planning director Rebecca Horner said in a December interview that “any zoning district that only allows single family units … would be a type of exclusionary zoning.”

Horner said the county is currently working on an affordable housing ordinance that would require a certain number of affordable housing units in every new development. She noted that the county planning department would prefer “to mix housing types and demographics together.”

“We want everybody to have equal opportunities to purchase in a neighborhood so that we don’t have neighborhoods that are single demographics,” Horner said.

The disparities between the rural area and the rest of the county have quickly become part of the ongoing debate about whether the board should change the county’s current land-use policies. The supervisors will likely update the comprehensive plan’s land-use chapter later this year.

The board’s three Republicans and many rural are advocates are opposed to any new changes in the rural area. Some have said they believe that any new development in the area would lead to “a domino effect” of development and increased suburban sprawl that could strain the county’s resource and damage the environment.

Meanwhile, some Democratic supervisors, including Wheeler, say they are open to allowing some new development in the rural area while taking action to permanently preserve environmental and agricultural resources there. That could include the possibility of adding new industrial-zoned land or higher-density housing than is currently allowed while downzoning other areas to something less than one home per 10 acres.

Wheeler said she disagrees that more development in the rural area will lead to more sprawl in the county if it’s implemented carefully.

“I believe we can put parameters in place to make sure that we have compact, cohesive communities and preserve open space and it’s not going to proliferate into sprawl,” Wheeler said. “We need to believe we can do this and do it well. But they’re just afraid to even try.”